Company News: Green Street Adds Advanced Sales Comps to College House, Driving Greater Platform Value

Housing Affordability: Lessons from History and Paths to Improvement

Housing affordability in the United States has entered one of the most strained periods in the last two decades, driven by a combination of surging mortgage rates, stubbornly high home prices, and wage growth that failed to keep up with home price appreciation.

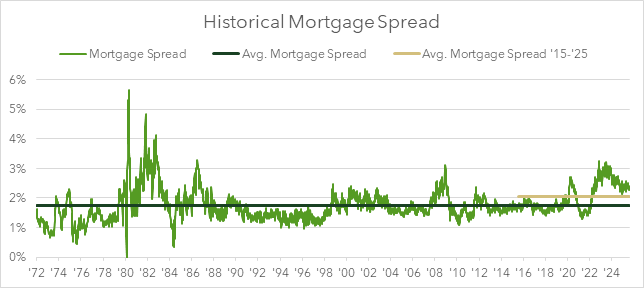

Since early 2021, total homeownership costs, which include mortgage payments, insurance, and taxes, have soared as a share of household income. The rise has been driven both by price appreciation and a surge in mortgage rates from historic lows below 3% to, at times, nearly 7% over the past few years. Today’s elevated rates stem from a combination of factors: a higher federal funds rate, a higher 10-year Treasury yield that serves as the benchmark for mortgage pricing, and a wider spread between mortgage rates and the 10-year yield. Historically, that long-term spread has averaged about 1.8%, but over the past few years has been well over 2% or even 3% (Figure 1).

figure 1

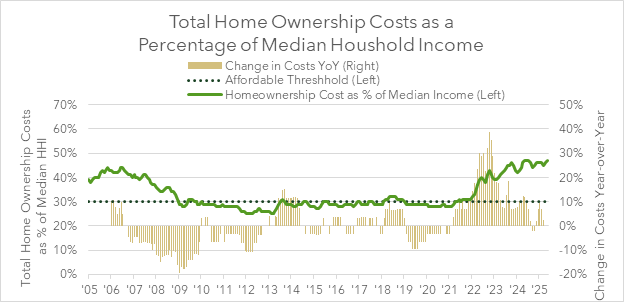

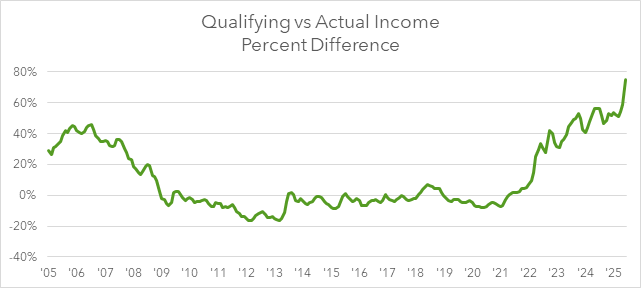

Homeownership costs now consume an unprecedented share of income. Throughout the 2010s and during the early phase of the pandemic, a typical mortgage payment hovered around 30% of median household income. Today, however, the average monthly payment is approaching nearly 50% of household income (Figure 2). Furthermore, the income required to qualify for today’s 30-year mortgage is over 75% higher than today’s actual median income, the highest the gap has been in the last two decades (Figure 3).

figure 2

figure 3

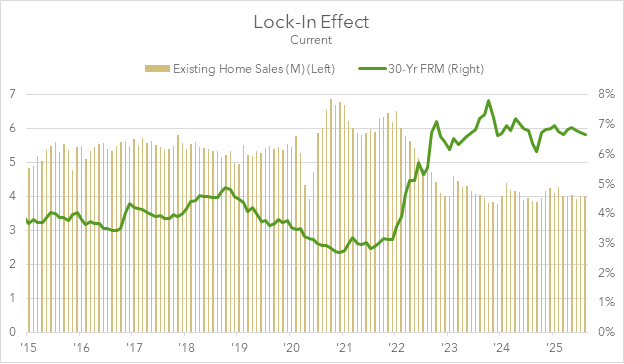

The Lock-In Effect

Housing affordability has been deteriorating for decades, but the recent surge in borrowing costs has turned a long-running imbalance into a much tighter, less fluid market. The sharp rise in 30-year fixed mortgage rates has triggered what’s known as the lock-in effect, where homeowners with low-rate loans are reluctant to sell and take on new mortgages at today’s higher rates, reducing for-sale inventory and keeping prices elevated (Figure 4).

figure 4

From a Homeowner’s POV

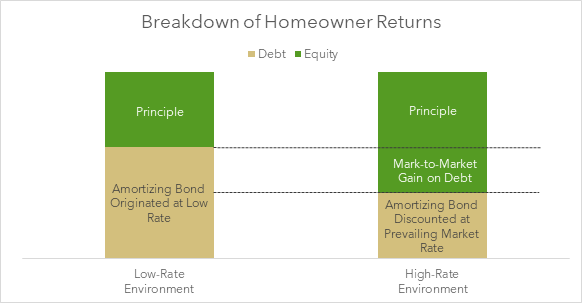

The persistence of the lock-in effect can be explained by how rates interact with the homeowner’s balance sheet (Figure 5). Taken from the perspective of one who is short a bond (the mortgage), higher rates have decreased the value of the current mortgage and therefore increased the value of the equity. Selling a home with a low mortgage rate is like buying back a deeply discounted bond at par, effectively paying a large premium to exit the position or forfeiting the beneficial mark-to-market gain on debt. For homeowners with lower rate mortgages, the reluctance to sell makes financial sense as the existing debt cannot be transferred to another property.

figure 5

Lessons from History

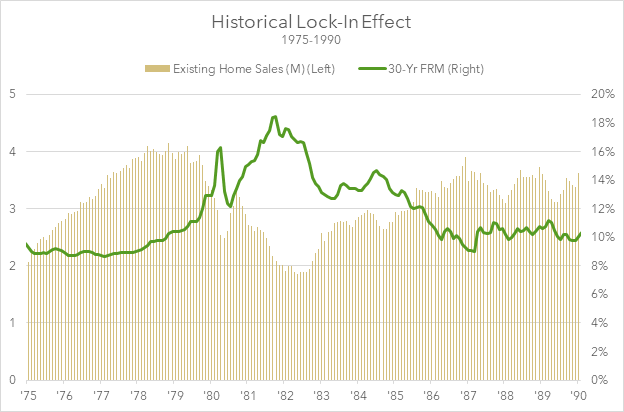

The lock-in effect isn’t new, and we’ve seen it before. During the early 1980s, mortgage rates climbed to nearly 18% as the Federal Reserve fought to contain the runaway inflation, making existing low-rate mortgages extremely valuable (Figure 6). At those levels, potential sellers clung to their loans and would-be buyers were priced out, causing existing-home sales to fall by almost 50% from the 1978 peak to the trough in 1982. Even though home prices continued to rise, the market effectively stalled until inflation subsided and the Federal Reserve cut the federal funds rate to around 9%, pulling 30-year mortgage rates down with it. The resulting drop allowed households to refinance, restored affordability, and gradually revived sales.

figure 6

Restoring Housing Affordability

Looking ahead, affordability is unlikely to improve quickly without a substantial change in underlying conditions. Fannie Mae now forecasts the 30-year fixed mortgage rate to end 2025 at roughly 6.4% and 2026 at 5.9% (though outcomes remain uncertain and depend on economic conditions). Home sales are forecast to stay near multi-decade lows even if price growth decelerates. According to J.P. Morgan, nominal wage growth is predicted to outpace home price growth in 2025, which could slowly ease affordability pressures, but that improvement will take time.

Real relief would likely require one or more of the following:

- Significant rate declines: As the 1980s show, mortgage rates need to fall well below current levels to unlock supply and restore affordability. A narrowing mortgage spread and lower Treasury yields could help, but a dramatic drop in rates is uncertain.

- Sustained income growth: A meaningful rise in median household income would help realign homeownership costs with borrowers’ ability to qualify for and service debt, provided wage growth outpaces home price appreciation. The 1990s offer a precedent, when steady income gains and healthier consumer balance sheets gradually restored affordability.

- Price corrections or expanded supply: Affordability would improve if home prices adjusted downward or if new construction meaningfully increased. In supply-constrained markets, policy reforms that ease zoning restrictions and accelerate development would be essential to boosting inventory. Price corrections also tend to occur during economic downturns. During the 2008 credit crisis, affordability improved only after a deep recession drove home values sharply lower. However, new-home construction faces its own limits today because high land and construction costs have pushed prices so high that many builders are struggling to move inventory even with increased supply.

- Financing innovations: Allowing mortgages to be portable or assumable could help ease the lock-in effect by letting homeowners transfer low-rate loans to new properties or buyers. However, most conventional US mortgages include due-on-sale clauses that prevent such transfers, and the securitization of loans further limits portability. While these ideas are gaining attention as potential ways to unlock housing supply, widespread adoption would require significant regulatory and structural changes in the US mortgage market.

Housing affordability today reflects both decades of structural imbalance and the more recent shock of higher interest rates. The resulting lock-in effect has slowed transactions, constrained supply, and magnified the affordability gap for new buyers. While past cycles show that conditions can eventually normalize, meaningful improvement will depend on a combination of lower borrowing costs, stronger income growth, and policies that promote new housing supply. Until those factors align, the path to widespread affordability will remain gradual and uneven.

Tyler Blue

—————————————————————————————————————————————